Double, Double Toil and Trouble from Macbeth by William Shakespeare

Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn and cauldron bubble. Fillet* of a fenny* snake, slice, muddy, fen-dwelling In the cauldron boil and bake; Eye of newt and toe of frog, Wool of bat and tongue of dog, Adder’s fork* and blind-worm’s* sting, forked tongue, poisonous worm Lizard’s leg and howlet’s* wing, owlet For a charm of powerful trouble, Like a hell-broth boil and bubble. Double, double toil and trouble; Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

Macbeth by John Martin, English, ca 1820. Scottish National Gallery, UK.

Let’s Dive In!

When it comes to Shakespeare, the wonderful thing is how much he is a part of our everyday speech, though few of us know to whom we owe phrases such as “a wild goose chase” (from Romeo and Juliet). I have attached a brief list of words and phrases that are in common parlance today, and that were first recorded in English among the pages of the First Folio, the 1623 compilation of Shakespeare’s plays; this list represents a smattering of Shakespeare’s contribution to our language. In all seriousness, you cannot read any great work of literature post-1616 without finding that the author owes a debt to Shakespeare.

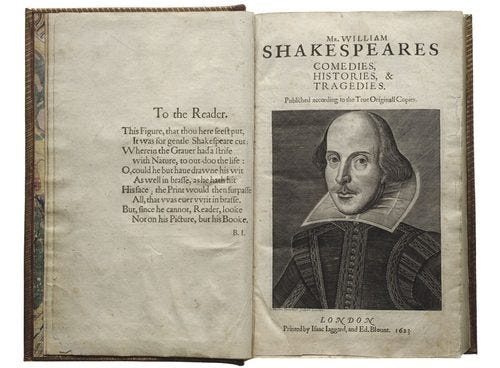

Title page from the First Folio, 1623. Here is a link to Folger Shakespeare Library where you can read more about this inestimable treasure.

Macbeth is one of Shakespeare’s most famous tragedies and is often included in high school curricula. I will offer here a few historical tidbits to illuminate the setting and subject matter of this play.

The play was performed around the year 1606, not long after King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England, following the death of Queen Elizabeth I. Shakespeare’s troop of actors (think business associates, highly professional) had been known as the Lord Chamberlain’s Men under the queen, the Lord Chamberlain being the queen’s closest advisor. Elizabeth I loved plays but did not trouble herself to attend the theatre: the theatre would be invited to come to her, performing at court upon countless occasions. King James being likewise a huge fan of theatre, Shakespeare’s company became known as the King’s Men. Shakespeare wrote Macbeth with King James particularly in mind. The setting is Scotland, James’s homeland. The themes abound with monarchical concerns such as loyalty, right of succession, ambition, warfare, justice, and authority. And it is full of witches, which was a favourite topic of study for James I.

And so, with the witches we come to today’s excerpt. In this scene, the three witches are circling around a boiling cauldron and throwing in various ingredients as they chant a spell. These “secret, black, and midnight hags” (IV.i.47) exert influence over Macbeth by suggesting that he will be king of Scotland in the future. Macbeth refers to the witches as “the Weird Sisters”; the word “weird” is rooted in the Old English “wyrd” and translates to “fate”. The play’s central question has to do with the dynamic between human freedom and the influences that, seemingly with such ease, sway the will from one thing to another. At the beginning of the play, Macbeth is lauded as the most loyal and selfless of thanes (Scottish lords), but, after a fateful encounter with the three “Weird Sisters” on the bleak moor, he rapidly pirouettes into a heartless regicide. Do the witches have the power to see into the future, or do their predictions come true because of Macbeth’s belief that they have true foreknowledge? Would Macbeth’s ambition have reached as far as the Scottish throne had he not heard the witches hail him as “King hereafter” (I.iii.50)?

If you are a fan of J K Rowling’s Harry Potter, Macbeth gets special mention because lines from this play were used for a sung chorus in the film adaptations—even Hollywood would be impoverished without Shakespeare references. Can you identify these famous lines? (See Further Up and Further In for more Shakespeare references.)

For Your Young Children

There is no shortage of beautiful autumnal poetry that you will enjoy with your young children, sans reference to cauldrons and poisoned frogs. Here are a few specimens that, I think you will agree, make a romp in fallen leaves inevitable! Thank you to Stephanie at This Intentional Home for these fall-ish poems for children!

Gathering Leaves by Robert Frost

Spades take up leaves

No better than spoons,

And bags full of leaves

Are light as balloons.

I make a great noise

Of rustling all day

Like rabbit and deer

Running away.

But the mountains I raise

Elude my embrace,

Flowing over my arms

And into my face.

I may load and unload

Again and again

Till I fill the whole shed,

And what have I then?

Next to nothing for weight,

And since they grew duller

From contact with earth,

Next to nothing for color.

Next to nothing for use,

But a crop is a crop,

And who’s to say where

The harvest shall stop?October’s Party by George Cooper

October gave a party;

The leaves by hundred’s came --

The Chestnuts, Oaks and Maples,

And leaves of every name.

The Sunshine spread a carpet,

And everything was grand,

Miss Weather led the dancing,

Professor Wind the band.

The Chestnuts came in yellow,

Th Oaks in crimson dressed;

The lovely Misses Maple

In scarlet looked their best.

All balanced to their partners,

And gaily fluttered by;

The sight was like a rainbow

New fallen from the sky.

Then, in the rustic hollow,

At hide-and-seek they played,

The party closed at sundown,

And everybody stayed.

Professor Wind played louder;

They flew along the ground;

And then the party ended

In jolly “hands around.”Merry Autumn Days by Charles Dickens

‘Tis pleasant on a fine spring morn

To see the buds expand,

‘Tis pleasant in the summertime

To see the fruitful land;

‘Tis pleasant on a winter’s night

To sit around the blaze,

But what joys like these, my boys,

To merry autumn days!

We hail the merry autumn days,

When leaves are turning red;

Because they’re far more beautiful

Than anyone has said.

We hail the merry harvest time,

The gayest of the year;

The time of rich and bounteous crops,

Rejoicing and good cheer.A Closer Look at the Poet’s Words…

Scholars down the centuries have yet to run out of eloquent statements about Shakespeare, so I feel rather shy about adding my two cents. You will not find any original comments here, but if something I say can bring into focus for a moment the brilliance and wisdom of Shakespeare—the greatest weaver of words to have ever lived, my embarrassment will be well rewarded. The real thrust of what I wish to urge is, firstly, Shakespeare is incredibly relevant. When the movements of the human heart, which are the same today as they were in 1606, are brought out of the dim cave and into the creative light of words, real progress toward truth is possible. The list of Shakespearean phrases and words that I have attached alongside this post will convince you and your students that Shakespeare is actually very close to us, albeit he has been dead for over four hundred years, but those words are just little blinks of light. You must read the plays and enter into the full drama in order to understand why Shakespeare is an expert on what it means to be human. Ideally, you will find the opportunity to both read Shakespeare and see also see his works performed. Which brings me to my second point: Shakespeare was never meant to be a book of pages. What you hold in your hands is the script for a theatrical production, meant to be produced on the scale of the biggest Hollywood blockbuster and performed for royalty. In the days before radio and television, friends and families would regularly entertain themselves by reading a play aloud together during the evening hours. I did not know this until, many years ago, I read Charlotte Brontё’s Shirley, in which the characters read aloud together Shakespeare’s history play, Coriolanus. Similarly, my father, who has acted in local theatre productions for decades, will occasionally get together with friends to read a play aloud, just for fun. The point is, unlike a novel, a play is meant to be spoken out loud in multiple voices joined together in time and space. To really “get” Shakespeare, you must realize that this is not a narrative but a play. So, gather a few people together to read a scene! Something happens when you do this—there is an unquantifiable element that will only present itself when you take the words off the page and bring them onto the stage. (Sorry for the rhyme there, but I might as well leave it because, you will notice, a rhyming couplet usually signals an arrival or departure in Shakespeare, and here I end my harangue!)

Alright, now that I have given you my pep talk, I want to say a few words about the form of this selection from the witches’ spell in Act IV, scene 1. I have only given you a portion of their incantation—you must read the scene in full to hear it all. As you say or hear the words, notice that the meter of the witches’ speech is different from the blank verse iambic pentameter that all the natural humans use in the play. Instead of the five beats of pentameter (penta=five) that operates with such ease in human speech, the witches speak in tetrameter (tetra=four), with four regular beats in each line:

DOU′ble, DOU′ble TOIL′ and TROU′ble

FI′re BURN′ and CAUL′dron BUB′ble

The effect of this tetrameter is sing-songy and as regular as a drumbeat; where pentameter lends itself to variety because of its odd number of beats, the even number of four beats is relatively inflexible and insistent. Shakespeare changes his meter here to make the audience feel the ‘weirdness’ or otherworldliness of the witches. You might have experienced this shift of vocal nuance with J R R Tolkien’s presentation of the speech of the de-naturalized character Gollum in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. The reader knows immediately that Gollum is deranged to some extent or other, simply because of the irregularities in his speech. Just so with the witches.

In addition to the change from pentameter to tetrameter, Shakespeare also rhymes the witches’ lines. The usual blank verse of Shakespearean characters is unrhymed, except in specific places to achieve an effect—pay attention, the rhyme tells the audience. Here, the witches’ rhymes are hypnotic and eerie, augmenting the suspense of this scene. The consonance in “double”, “trouble”, and “bubble” mimic the boiling of the cauldron, the repeated plosive consonants (d, b, t) breaking into the calm of the evening and causing the dead organisms that are being thrown into the pot to move tumultuously against the natural order of death. As the witches toss their ingredients into the cauldron, they list them aloud. They are all parts of animals and reptiles, often poisonous and associated with magic and evil. The diction of the list makes use of rhyme, alliteration, and assonance, but the lines are more punctuated, with minimal syllables. The final couplet is strengthened by this build-up of beats, and is lengthened by an extra off-beat syllable at the end of both lines:

FOR′ a CHARM′ of POW’′rful TROU′ble

LIKE′ a HELL′-broth BOIL′ and BUB′ble.

And with a repetition of the refrain, the spell goes on. Few representations of evil are so effective as those found in Macbeth.

Many thanks to

Fabian for his illuminating remarks about Shakespeare’s use of tetrameter and literary devices!Biography and History

There are many excellent biographies of Shakespeare written for children, so, in lieu of competing with these, I will keep my notes here brief and recommend a few books for you under the last heading in this post, “Additional Resources”.

Briefly then, William Shakespeare was born in Stratford, England in the springtime, 23 April 1564. His father, John Shakespeare, was a successful glove-maker and local politician. Shakespeare attended school till he was fourteen. At the age of eighteen, he married a lady named Anne Hathaway. The couple had three children, Susanna, and twins, Hamnet and Judith. From 1585 until 1592 there are no records of Shakespeare’s whereabouts; these are called the Lost Years. In March of 1592, however, Shakespeare’s play Henry VI, Part 1 was performed at the Rose Theatre in London to great acclaim. Within five years of this success, Shakespeare could afford to purchase for his family the second largest house in his hometown of Stratford. When he retired in 1613, his fame was unmatched, and he enjoyed a few quiet years before his death in 1616. The legacy of his work is an incalculable enrichment of the English language, and the rendering into words the deepest thoughts and movements of the human heart.

Portrait of William Shakespeare, attributed to Charles Cobbe (1686-1765)

Tools and Vocabulary for Poem Analysis

Consonance: from the Latin consonare, to sound together. Consonance is the repetition of a pattern of consonants, eg leave – love; linger - longer

Assonance: Also called interior rhyme, assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds, apart from the consonants around them. Assonance is usually found in the stressed syllables of the verse meter. (So, for example, if a poem is in iambic meter, the repetition of the vowel sounds will be in the second syllable of each iambic foot; if the meter is anapestic, the assonance will usually occur in the third syllable.) The effect of assonance is to unify or smooth the verse. Notice the repetition of the short <i> sound in “still” and “unravished”, and the repetition of long <i> sounds in “bride”, “quietness”, “child”, “silence”, and “time” in these lines from “Ode on a Grecian Urn” by John Keats: “Thou still unravished bride of quietness, / Thou foster-child of silence and slow time”.

Alliteration: Alliteration is the repetition of initial consonant sounds. This literary device hearkens back to Old English composition. It unifies and moves the verse forward, much like rhyme, and may be called front rhyme. The first line of our Shakespeare selection is an example of alliteration: “Double, double, toil and trouble”.

Iamb, iambic foot: The basic accentual-syllabic pattern of English verse is the iamb, an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable, “di-DUM”. Each of these sets of two syllables is called an “iambic foot”. You can associate meter with marching, and maybe that will help explain why we call each unit within the verse a “foot”.

Trochaic tetrameter: This meter is made up of four trochees per line of verse, “tetra” from the Greek word for “four”. Since each trochee contains one stressed, or beat, syllable and one unstressed, or off-beat, syllable, this meter has four beats per line: “DUM-di, DUM-di, DUM-di, DUM-di”.

Trochee: The inverse of an iamb, a trochee is a two-syllable metrical unit that begins with the stressed syllable and ends with the unstressed syllable: DUM-di. A poem that uses trochees for its basic structure is said to be in trochaic meter.

Plosive: In English, the letters t, k, and p are voiceless plosives, and d, g, and b are voiced plosives. If you think of the word “explosive”, you will have the basic idea of this linguistic descriptive—these letters, when spoken, emit outward either sound or air or both, in contrast to letters like m or ĕ, in which the sound is more contained within the mouth. Plosives are effective poetic tools for mimicking action that is kinesthetic or disruptive, as, in our excerpt, the boiling of the cauldron.

Further Up and Further In

Practice identifying assonance, consonance, and alliteration in a poem of your choice. I recommend choosing a poem by John Keats for this exercise. His verse is as mellifluous and sonic as English verse can possibly be, and you may identify echoes of Shakespeare in it.

Allusions to Shakespeare are ubiquitous in English literature. When you read Shakespeare, you place yourself in the company of all your favourite authors. Your challenge over the next couple of weeks is to look out for Shakespeare quotes woven into the pages of your favourite stories. To give you an idea of what this may look like, here are two examples of this most thrilling work of Shakespearean detection that I have come upon in the past month:

Anne of Avonlea by L M Montgomery (Canadian—just saying)

In Chapter XII “A Jonay Day”, Marilla is trying to console a disconsolate Anne by offering her food. Here is their dialogue:

“‘Just come downstairs and have your supper. You’ll see if a good cup of tea and those plum puffs I made today won’t hearten you up.’

‘Plum puffs won’t minister to a mind diseased,’ sighed Anne disconsolately; but Marilla thought it a good sign that she had recovered sufficiently to adapt a quotation.”

And what, you ask, is the quotation? Read Macbeth a time or two, and you will know.[1]

The Unselected Journals of Emma M Lion, Volume 1 by Beth Brower

On March 9th, Emma recounts a conversation with her cousin Arabella, the conclusion of which is as follows:

“When I began to fret we might be found out, Arabella looked at me with her forget-me-not blue eyes and said, ‘Emma, screw your courage to the sticking place.’

Quoting Lady Macbeth is not, perhaps, a morally comforting thing, but it did the job with aplomb.”[2]

Again, you know where to look to find the scene and line.

NB It is no coincidence that I identified two quotes from Macbeth this month, because it was Macbeth that I recently read. The Shakespeare you are reading will the Shakespeare you are finding. I recommend A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest from the comedies, Hamlet and Macbeth from the tragedies, and Henry V from the histories. But don’t stop there! Shakespeare is rather like the Bible, in that you can spend your entire life reading him and he will never grow wearisome.

Also, NB, you will find Shakespeare references not only in novels and poems but in music lyrics and speeches.

[1] Montgomery, L M. Anne of Avonlea. Random House, 2003. The Shakespeare reference may be found in Macbeth, Act V, scene 1.

[2] Brower, Beth. The Unselected Journals of Emma M Lion, Volume 1. Rhysdon Press, 2019. The Shakespeare reference may be found in Macbeth, Act I, scene 7.

Additional Resources

Picture books:

The Bard of Avon by Diane Stanley

William Shakespeare & the Globe by Aliki

Will’s Words: How William Shakespeare Changed the Way You Talk by Jane Sutcliffe

Encyclopedic or biographical books:

Shakespeare by DK Eyewitness

Who Was William Shakespeare by Celeste Mannis, from the Who Was? Series

William Shakespeare from USBORNE Young Reading

Novels set in Shakespearean England:

Stage Fright on a Summer Night (Magic Tree House Series) by Mary Pope Osborne

The Shakespeare Stealer by Gary Blackwood

Cue for Treason by Geoffery Trease (I love this book!)

Books that retell Shakespeare’s plays for children—an excellent way to convey the plot before reading the script:

The Usborne Complete Shakespeare

Tales From Shakespeare by Charles and Mary Lamb

Various titles by Edith Nesbit

Resources for reading Shakespeare with your children:

How to Teach Your Children Shakespeare by Ken Ludwig

Read Aloud Revival Podcast with Sarah Mackenzie, Episodes 171, 206, 241, 206, 265, and 266

I'm loving the Emma M Lion quote!

I forgot to say how happy I was to see the Anne Shirley quotation. And how much I agree that Shakespeare needs to be performed. Students who protest they can't understand him are always surprised how they can unlock the meaning just by assigning parts and doing a simple reader's theater in class.